Paul Jefferson, one of the earliest humanitarian deminers said “a landmine is the perfect soldier: Ever courageous, never sleeps, never misses”. The simplicity and cost-effectiveness of mines are major factors in explaining the widespread use of mines throughout the numerous countries that are now faced with dealing with the mine contamination problem.

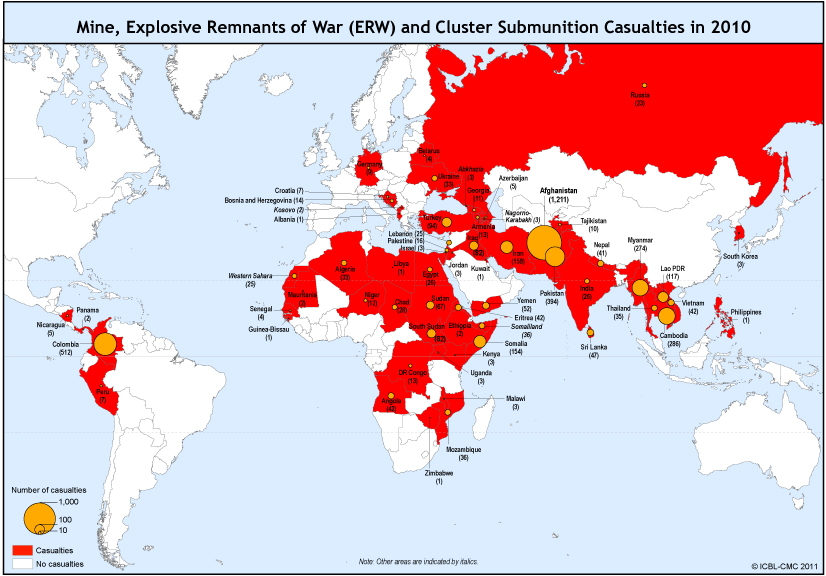

Detection and removal of antipersonnel landmines is, at the present time, a serious problem of political, economical, environmental and humanitarian dimension. As this map shows, there is still a long way to go before the world is free of anti-personnel landmines.

The following facts reflect the seriousness of this problem:

- It is estimated that there are 110 million land mines in the ground right now. An equal amount is in stockpiles waiting to be planted or destroyed.

- Mines cost between $3 and $30, but the cost of removing them is $300 to $1000.

- The cost of removing all existing mines would be $50- to $100-billion.

- According to the ‘International Campaign to Ban Landmines network’, more than 4,200 people, of whom 42% are children, have been falling victim to landmines and ERWs annually in many of the countries affected by war or in post-conflict situations around the world.

- According to Landmine Monitor, number of landmine and UXO casualties was 11,700 in 2002 and 4286 in 2011.

- Mines kill or maim more than 5,000 people annually.

- Mine and explosive remnant of war casualties occur in every region of the world, causing an estimated 15,000 – 20,000 injuries each year.

- One deminer is killed and two injured for every 5000 successfully removed mines.

- Overall, about 85 per cent of reported land mine casualties are men, many of whom are soldiers. However, in some regions, 30 per cent of the victims are women.

- Mines create millions of refugees or internally displaced people

- The areas most affected by land mines include: Egypt (23 million, mostly in border regions); Angola (9-15 million); Iran (16 million); Afghanistan (about 10 million); Iraq (10 million); China (10 million); Cambodia (up to 10 million); Mozambique (about 2 million); Bosnia (2-3 million); Croatia (2 million); Somalia (up to 2 million in the North); Eritrea (1 million); and Sudan (1 million). Egypt, Angola, and Iran account for more than 85 per cent of the total number of mine-related casualties in the world each year.

- Until recently, about 100 000 mines were being removed, and about two million more were planted each year.

- If demining efforts remain about the same as they are now, and no new mines are laid, it will still take 1100 years to get rid of all the world’s active land mines.

- For the military, mine detection rates of 80% are accepted since all the military needs are a quick breach in a minefield. For humanitarian mine clearing it is obvious that the system must have a detection rate approaching the perfection of 99.6%.

- The most common injury associated with land mines is loss of one or more limbs. In the United States, the rate of amputation is 1 for every 22 000 people. In Angola, it is 30 for every 10 000.

- In many of the most affected areas of the world, agriculture is the mainstay of the economy. Land mines are planted in fields, forests, around wells, water sources, and hydroelectric installations, making these unusable, or usable only at great risk. Both Afghanistan and Cambodia could double their agricultural production if land mines were eliminated.

Egypt as a Case Study

Egypt has been listed as the country most contaminated by landmines in the world with an estimate of approximately 23,000,000 landmines. Egypt is also considered as the fifth country with the most antipersonnel landmine per square mile. This serious problem hinders economic development of rich areas in the north coast and red sea.

The area of north coast was contaminated as a result of hostilities between 1940 and 1943 involving Britain and its allies (including Egyptian forces) fighting German and Italian forces for control of North Africa. The areas to the east, including the Sinai Peninsula were contaminated between 1956 and 1973 due to hostilities between Egypt and Israel. These rich areas represent 22% of the total surface of Egypt. Development projects in these areas are significantly constrained by mine and UXO contamination and the civilian casualty rate seems high in proportion to the populations in these areas. The contaminated areas enjoy great oil and mineral wealth such as petroleum and Natural Gas. The problems of landmines lead to the contribution of the North Coast to 14% only of the total oil and natural gas production in Egypt.

Moreover, in Egypt agriculture is one of the mainstays of the economy. Landmines are planted in fields, around wells, water sources, and hydroelectric installations, making these lands unusable or usable only at great risk. Egypt could increment its agricultural production if landmines were eliminated from the contaminated regions. The mines in a wide coastal strip, all the way to the Libyan border (and beyond), nearby coastal regions of Suez Canal Zone such as salt lakes and Red Sea coast prevent use of hundreds of thousands of sq. km. of agricultural land, prevent travel on thousands of km. of roads and deny access to potable water. These facts reflect the level of seriousness of landmines in Egypt. The contaminated areas in the North Coast, Gulf of Suez and Red Sea coasts are now being reclaimed for economic development making mine clearance an urgent priority for the Egyptian government.

The landmine and unexploded ordnance (UXO) problems in Egypt are unique due to the following facts:

- Egypt suffers alone from more than 20% of the total number of the landmines in the world.

- A huge area of land is affected – some estimates put the total at about 25,000 sq kilometres.

- The age of much of the material is up to 60 years.

- Much of the mines and UXO is covered by thick deposits of mud or sand so that conventional detection techniques are often of little value.

- Landmines can shift placement in soil over time and due to weather conditions; soil type can also pose a challenge to landmine detection and clearance. In sandy soil like the contaminated areas in Egypt, wind can shift sands dramatically, and the fine grit of sandy soils can rapidly wear equipment. Moreover, excavating and sifting of soil for mine-size objects is more difficult in hard clay soil or rocky areas. Some soils have high mineral content that interferes with standard detection equipment.

- The contaminated areas are rough terrain with steep inclines, ditches and culverts that make moving around sites by individual deminers or mechanical equipment difficult and even dangerous.

- The climate is extremely unpleasant for deminers. Temperatures to 55 degrees Celsius are common. The conditions are either dusty and sandy or muddy along the coast and sometimes both. The muddy areas and marshes are particularly difficult to deal with as it is often impossible to stand in the mud.

- Another challenges come from the type of landmines as there are hundreds of landmine types. Mines can have metal, plastic, wood, or even football casings. In Egypt, casings and components should have been degraded over time, altering their detection signature and creating uncertainty as to how mines will stand up to clearance.

- Windblown sand burying mines and fragments up to 2 meters deep in places. Deeply buried mines (>30 cm) are difficult to detect by conventional methods, and may even be missed by clearance equipment.

- Due to the lack of maps, the exact location of minefields and placement of mines are not available. This information is rarely well recorded. Even though these maps are available, they might not be useful due to nature of the dusty soil in the affected areas that make the mines change their locations. If these maps are available, they can be used as guidance only with certain level of uncertainty. The British Ministry of Defense has apparently provided the authorities in Egypt with copies of surviving maps of known minefields and supporting information on the types of mines laid and the techniques used by the Commonwealth forces during the war. However, it is unknown how many minefields had surviving maps [Ref.]. Germany and Italy have not provided minefield maps to the Egyptian authorities. However they keep supporting Egypt’s mine clearance efforts with equipment and training.

- Egypt has not signed the Mine Ban Treaty. Egypt participated in the Ottawa Process as an observer. Egypt’s reasons for not signing the ban treaty have been stated in various international fora. Arguments put forward by Egypt include that the treaty does not take into account “the legitimate security and defense concerns of states, particularly those with extensive territorial borders” which need landmines to protect against terrorist attacks and drug traffickers [Ref.].

More information: Alaa Khamis, “Minesweepers: Towards a Landmine-free Egypt“, 17.1 Spring 2013 issue, Journal of ERW and Mine Action.